The stock market goes up, and it goes down. Here’s how these stock markets work, and who decides the share prices.

It starts with buyers and sellers (like you)

The ecosystem all starts with buyers and sellers of individual shares. To understand how this works, you need to understand that every share represents a tiny slice of ownership in a business.

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) is the marketplace where this buying and selling happens. It has some of the country’s biggest companies listed on it, like Vodacom, Standard Bank, Old Mutual, Mr Price, Clicks, and Woolworths – and other, not so familiar names that are still big, global businesses.

Say you’re an investor buying a share in Vodacom on the JSE. This means you own a tiny portion of the company, and you can cash in on a very small portion of Vodacom’s profits. This is also known as ‘qualifying to receive dividends’.

Investors in shares – including asset managers in charge of equity funds – have a lot to choose from. They’re looking for shares in those companies that are going to grow over time.

The JSE, like other stock exchanges, provides a platform that lets investors buy and sell these shares. The system is effectively a huge auction that takes place every trading day. As with all auctions, you’re trying to pay as little as possible as a buyer, and trying to get as much as possible as a seller.

Who’s feeling the pressure?

For a trade to happen, buyers and sellers need to agree on a stock price. This leads to buyers competing with other buyers, and sellers competing with other sellers.

Say you’re this investor and you decide to sell your Vodacom shares. You offer to sell at a certain price, but realise that it’s too high and there are no takers.

Instead, a buyer enters a lower price as their bid. This creates a gap between what you want as the seller, and what your buyer is prepared to pay for your shares. Since this is an auction, there’s a possibility that another seller offers the shares at a slightly lower price than yours, and another buyer bids slightly more than the first buyer. This offering and bidding goes on during the day, in real time.

The price at which trades happen depends on who feels the most pressure. If there are many more buyers, they have to increase their bids to be competitive; if there are lots of sellers, they’re forced to drop their offer prices.

So how are stock indexes constructed?

A stock market index is an average of share prices within that group of shares. The Top 40 index, for example, is a weighted average of the share prices of the 40 biggest listed companies.

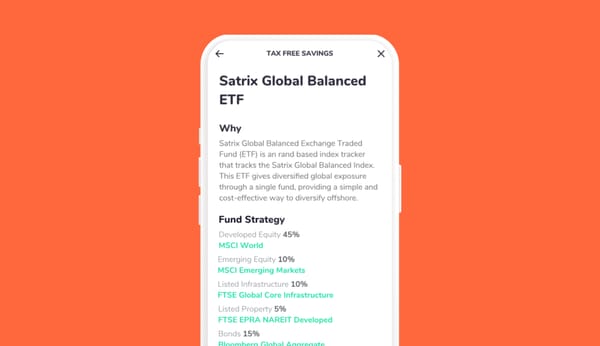

A fund like the Satrix 40 ETF goes up and down with the movements of the Top 40 Index.

The JSE system calculates these ‘average’ prices on a real-time basis, second by second. The buying and selling pressure of all those investors trading those 40 shares is what moves the index up and down.

A difference in opinion

Every day there are investors – individuals and professionals alike – who want to sell shares, and others who want to buy those same shares. Why’s there such a difference in opinion?

- After analysis, some investors might believe that a business is set to grow and become more profitable, while others might worry the business is going to shrink.

- Even if they agree it’s a great business, some might believe the shares are overpriced today, while others might believe they still offer value.

- Automated systems that are put in place by big asset managers sometimes trigger offers and bids based on predetermined programmatic rules.

- Sometimes selling pressure has less to do with opinion than cashflow – for example, a fund needing to sell shares to cover investors selling out.

Ultimately, all the price movements of funds and indexes around the world start with offers and bids on specific individual shares. Stock exchanges are amazing real-time auctions that let investors compete to get the best deals – that’s why, over time, investing in equities has shown the greatest growth potential.

So if you know that you can hold out for more than 3 years (the longer, the better!) and you’re looking to reap the rewards of inflation beating returns, consider putting some money away into the equity fund on your Franc portfolio.